Sounds Green to Me! A Case Study of 'Rendering Sustainable' in US Apparel Websites

Author: Matthew Porter

Publication date: 7 September 2021

In an era of increasing environmental concerns, the fashion industry has found itself at the center of the debate as one of the more prominent culprits with textile goods. Despite accounting for approximately 8% of landfill usage in addition to detrimentally affecting waterways via the improper disposal of dyes or other chemical agents, there remains a potential beacon for hope in correcting some of the major affronts to our environment. Scholarship aiming to theorize and implement more sustainable practices (specifically in fashion or otherwise) largely focuses on the tangible impacts of irresponsible eco-social interactions (pollution, microplastics, etc.) and traces these ills in logics of Western modalities of consumerism, industrialization, and production [1]. Then, the propositions for recourse typically entails shifts in behavioral and/or infrastructural norms such as zero waste design [2], bio-textiles, recycling campaigns, consumer education etc. . However, these noble recommendations may very well put the cart before the horse in terms of devising solutions that are both actionable and understandable.

On one end, consumers are becoming increasingly environmentally conscious. As such, research has sought to investigate consumer motivations and purchase behaviors surrounding sustainable products. Yet, conclusions suggest that even with a rise in consumer consciousness, this does not necessarily correlate to a change in purchase behavior especially if higher cost is a factor. However, the importance of how pertinent actors—be they executives, designers, or consumers—learn and enact sustainability is oftentimes overlooked. Particularly, the communicative aspect of the sustainable platform is the point of interest. How do consumers come to parse authentic sustainable praxes versus greenwashing? How can firms expect consumer buy-in to their goals if there are gaps in articulations and perceptions surrounding sustainability? Or, to what degree are consumer concepts of sustainability shaped by the messages output by their favorite brands?

Ostensibly, there is a sustainability culture in the modern fashion sphere but there is only an overly broad thematic consistency in how firms align themselves with the cause and, likewise, consumers. A brand that says that it is “sustainable” or “zero-waste” or “ethical” intends to capture this class of eco-conscious consumers. But this consumer base is far from monolithic. The way in which one views, understands, or interprets sustainability is variable depending on factors such as location, age, education level and type, and class among other social aspects. These demographic factors can also correlate to preferential terms for a given population. This immediately should give pause to consumers, educators, and brand agents alike when using such terms, especially the generic descriptor “sustainable”. Although organizations such as B Corps have sought to codify some semblance of ethical and eco-friendly standards, the broader landscape of sustainability branding is left to the whims of brands’ individual marketing teams. Similarly, pushes to legally define sustainability are on the rise. Yet in the panoply of environmental marketing recommendations per the Federal Trade Commission, certain terms like "sustainable" and "organic" still lack rigid criteria.

These sustainability buzzwords are not mere synonyms. They carry subtle yet powerful interpretative weight that can often lead to confusion about what the brand actually stands for or approaches its goal. Anthropologist, Kedron Thomas, posits that these divergences even contribute to conceptual disjunction within fashion firms. Specifically, she highlights how the idiosyncratic interpretations of sustainability (and even fashion in general) between designers and the business suite are often out of sync. Whereas the business side tends to articulate sustainability along lines of efficiency, waste-reduction, and human capital, the design side tends to articulate sustainability in opposition to traditionally capitalistic orientations to unbridled growth and promote a vision of quality and artistic intimacy. Organizationally speaking, these disjunctions are not limited to the fashion industry nor to the conversation on sustainability and therefore are unsurprising [3]. Along these lines though, zero-waste researcher, Holly McQuillan, cautions overreliance on terminology as being fully representative of what they seem to suggest. She notes that marketing frameworks such as "zero-waste", for example, contain within them a logic of a growth in production as opposed to reduction as the name implies. The contention with such realities have led some brands to reject the label of "sustainable" entirely.

The sustainability discourse in the fashion industry is complicated along the commercial and creative axes. This definitional fuzziness trickles down to the consumer, but this has not deterred companies from presenting themselves in some flavor of sustainability. To be clear, the construction of a brand's—inward or outward—sustainable presentation is not simply one of verbiage. Rather it is an amalgamation of multiple assets that allows them to render sustainable. Borrowing Lily Irani's [4] framework of "rendering entrepreneurial", the concept of rendering is cultural and strategic business practice by which firms seek to establish themselves as embodying, enacting, and reproducing a sought-after social value and leverage that image for both economic and cultural clout. Thus, the questions become: what are the variations in which contemporary fashion firms package notions of sustainable practice? And what are the limits, overlaps, oversights, and/or exclusions of these “aesthetics" —that is, the linguistic and visual construction— of sustainability as it pertains to consumer audiences?

Method

Traditionally, the store and print ads have been the primary source for consumer engagement with brand messaging. Recently though, these media have been largely supplemented if not subsumed by the digital sphere. The digital space, whether it be through websites or sponsored advertisements have come to be the driving force in how consumers interact with brands and receive brand messages. Therefore companies’ websites serve as interactive, although limited, “digital environments” [5]. Especially in the wake of Covid and a rampant growth in online consumerism in general, the website allows for a layered feel of brand-customer interaction as an outlet for marketing, documentation of business narratives, as well as a point-of-sale.

As such, a netnographic approach to 5 sustainable fashion brands' (The North Face, Patagonia, Everlane, Taylor Stitch and Eileen Fisher) websites was undertaken in order to move towards a better understanding of how fashion brands render sustainable through diction, imagery, and other company features such as services. Sites were observed intermittently between January 2021 and May 2021.

The brands selected are all US-based apparel retailers that employ sustainability as a crucial part of their brand image. These brands all resided in the contemporary-bridge price point [6]. brands in this price point would be more likely to display a more curated sustainable messaging as they would not be marketing to a mass-consumer base. At the same time, these brands are not excessively niche so as to yield hyper-specific brand messaging. Additionally, the selection of two activewear brands alongside three sportswear brands similar in price range generated potential to more readily examine overlaps and disjunctures both within and across categories.

Each of the firm's sustainability messaging were examined to preliminarily categorize them within a sustainable modality to establish a baseline for key features in their messaging. Sustainable modality here refers simply to the way(s) in which the firm generally stakes itself on sustainability and were ascertained by the presence of specific programs/services or recurring verbiage. These were classified as: Ethical Sourcing, Zero Waste, 2nd Hand, Mending, Re/Upcycling, Small Runs.

Following this categorization, in depth content analysis of the site as a digital location was conducted via noting the prominence of sustainability messaging/imagery, attempts toward consumer engagement [7], and documentation of images and design elements such as color schemes or fonts. The sites' copy provided the primary source of analysis. Prominent visual and textual elements such as splash pages, lightbox pop-ups, and readily navigable texts were the primary source for coded elements. Longer-form informational text such as blog posts were considered thematically. The following predetermined codes were developed following the review of several prior research studies (e.g. Park & Lin, 2018; Lascity & Cairns, 2020) on sustainable branding and via a categorization model set forth by Todeschini et al. (2017) in order to further situate the firms’ sustainable personas.

1) Appeal to quality (utility)

2)Appeal to quality (luxury)

3) Appeal to innovation/technology

4) Appeal to fashion

5) Appeal to environmentalism

6) Appeal to empowerment (Consumer)

7) Appeal to Empowerment (Other person)

8)Appeal to social equity

9) Appeal to education (data)

10) Appeal to education (narrative)

11) Appeal to community

12) Appeal to customization

a) Altruism

b) Egoism

c) Circular Economy

d) Lowsumerism (or small run)

e) Sourcing

f) Second Hand

g) Mending

h) Zero-waste (or waste in general)

i) Recycle

j) Upcycle

Findings

Patagonia

Sustainable Buzzwords: Impact; Responsibility

Primary Appeal(s): Data Education; Environmentalism; Altruism

When research regarding sustainability is on the table, Patagonia is typically one of the brands to be investigated which is likely due to their early and vocal alignments with environmentalism. Patagonia is an active, outdoors, and lifestyle brand offering mens, womens, and kids apparel alongside their platform Worn Wear which is a service for second-hand product offerings. Patagonia offers a multifaceted and robust approach to sustainability. Their site features a wealth of nature imagery and candids of bulk piece-goods alongside a bold, modern font, and stark black shapes. By emphasizing "Stories", videos, and social media feeds heavily throughout the site, Patagonia constructs a captivating and interactive space.

Through these channels Patagonia actively centers the role of the consumer as a participant through pithy copy like "Buy Less. Demand More" or "Join the fight against fast-fashion". Moreover, Patagonia engages in antithetical language as a way to establish their credibility through articles such as "Can we stop greenwashing" which evidently would insinuate that they do not engage in this practice. This almost antagonistic or manifesto style of writing grounds Patagonia as active and vocal in this quest for what they consider to be better environmental practices.

What's more, several layout features aid in rendering Patagonia as a 'responsible' firm. On the apparel front, although "Shop" is the first item in the menu, "Used Gear" is the first link to access products in the main body of the home page. Patagonia also leverages their practices of corporate social responsibility (CSR) as an on-going element of their brand. While other brands alluded to other initiatives (The North Face donning a rainbow logo for the month of June or Everlane having a DEI link in the footer), Patagonia's brand brings CSR to the forefront. For one, the menu the tabs read: Shop, Activism, Sports, and Stories. These orientations are articulated through the incorporation of descriptive blog posts, video clips, and explicit data that visualizes and displays to the consumer their efforts in action. These media assets not only serve to bolster the lifestyle throughlines of the brand, but also serve as a means to educate consumers about the impacts of their sustainability and ethical measures that underscores their perceived outspokenness. While there are clear pathways to access products, the lifestyle content on the site upstages the shopping elements. This proportion of features may also contribute to the perception of Patagonia as a first-to-mind sustainable brand.

Eileen Fisher

Sustainable Buzzwords: Organic; Sustainable

Primary Appeal: Environmentalism; Sourcing

Eileen Fisher is a contemporary womenswear brand offering women's apparel and accessories. Over time they have offered various garment recycling programs and education for product care. Upon entering the Eileen Fisher (EF) site, you will be greeted by a fresh white layout complimented by thin sans serif fonts and a video of a blonde woman in a wheat colored, linen, gingham jumpsuit lazing by on a beach. The copy reads: "A simple wardrobe. A sustainable life." The combination of natural tones and fabrics conveys a message of natural simplicity as their read of sustainability. The mellow color palette, and images that emphasize the 'rawness' of the textiles pictured enhance the mood of being a brand whose stake to sustainability hinges on the natural and their sourcing of "organic" fibers.

From a click on the initial video or by navigating to the "Behind the Label" tab on the site header, you will arrive upon EF's portal of sustainability messaging. Possible routes include information on the location of their farms, their traceable cotton initiative, and other initiatives such as their sourcing of Peruvian knitters to product-care resources. On these pages, the images are more explicit, depicting fields or close-ups shots of cotton plants. The theme of the content under the Organic Fibers tab invokes sentiments of purity and cleanliness of the fibers that go into making their clothes. Through this, EF's sustainable identity exhibits a focus on where the components of their products come from with a hint of emphasis on materiality.

Unfolding alongside this, EF also centers their sustainable sourcing with regards to appeals to community/collaboration with their farmers and small factories primarily through the usage of educational narrative vignettes. Through the inclusion of videos and quotations from the farm or factory workers they source from such as "We feel like we're growing for Eileen...There's satisfaction in knowing where your cotton is going" implying a participatory labor dynamic. Through quotes such as "Knitting sweaters is a nuanced art" EF's sustainability persona evokes a creative sustainable angle that Thomas describes through the focus of facializing their craftsmen and workers which positions the product relationally. In this way, the injection of the artistic allows for EF to be read as a creative or fashionable brand despite its simplicity.

At the same time, EF also renders sustainable in a more corporatized way. While using data less than the other brands surveyed, EF is one of the few that breaches a discussion of price and economics of scarcity. They note: "We pay more for organic materials—and you do too...we know we can make the greatest impact by paying premiums directly to farmers..." Points such as this one go towards trends of transparency and act as a recognition of the price dilemma and justifies why the higher cost is worth it.

The North Face

Sustainable Buzzwords: "Re"—

Primary Appeal(s): Environmentalism; Recycling

Secondary Appeal: Egoism

The North Face is an outdoors, lifestyle, and utility brand with mens, womens, and kids apparel offerings. They feature The North Face Renew as a service to mend, upcycle, and resale North Face products. Similar to its competitor Patagonia, The North Face (TNF) is also a first-to-mind representative of the sustainability agenda although within the past few months the famed outdoors brand has been criticized for disingenuous practices. Nevertheless, TNF presents an incredibly robust but complex model for their sustainable alignments.

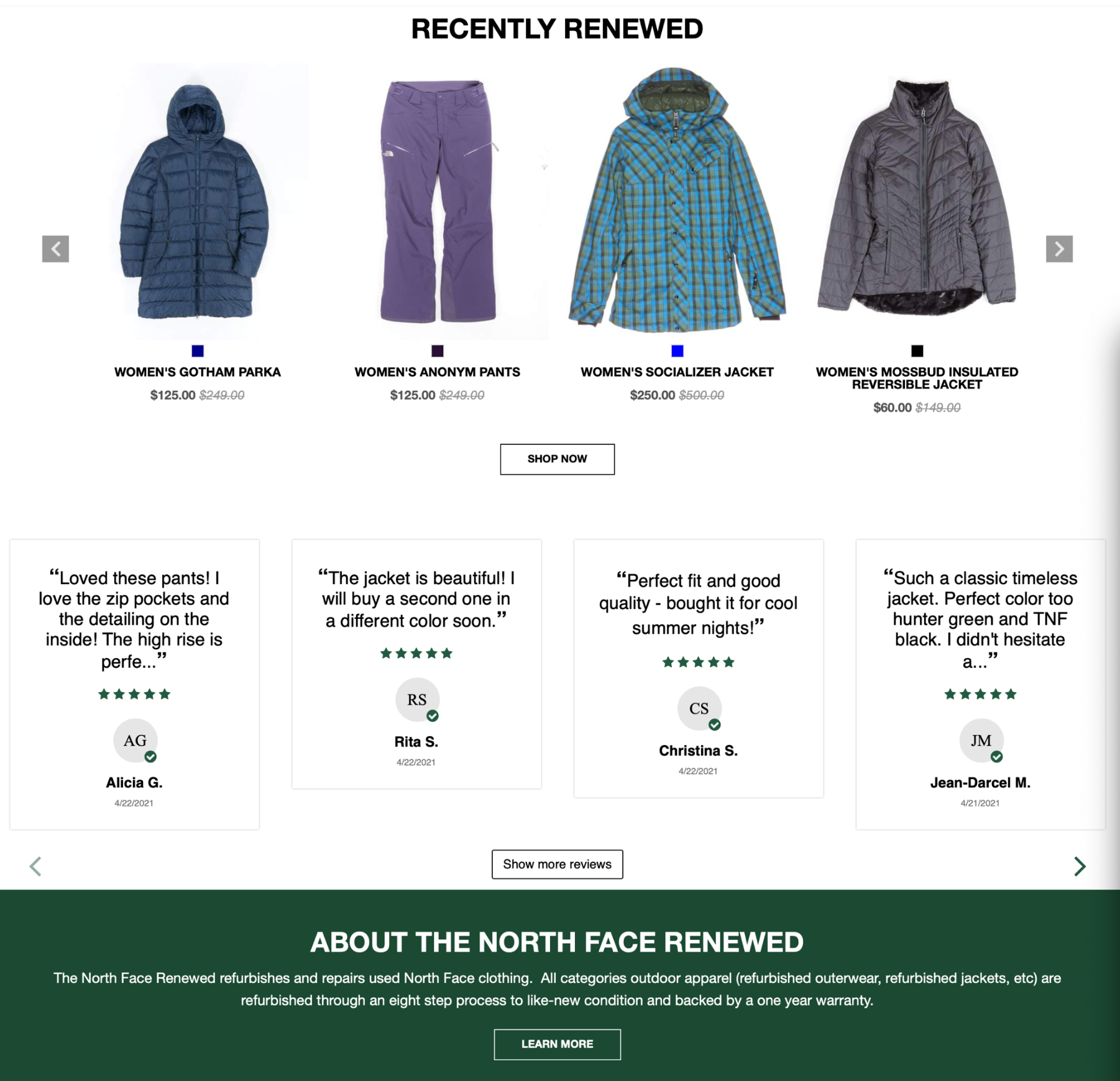

Because TNF is by way of its product offerings aligned with nature and the outdoors, it cannot be surely stated that such images are intentionally part of their sustainable messaging or purely coincidental. Sustainability messaging for TNF can be accessed under their About Us tab in the header or through their North Face Renewed tile at the bottom of the page. This program, essentially a diffusion line of TNF proper, can be considered a hub for their sustainability conveyance. Despite being a central resource for showcasing their mended and upcycled goods, The North Face Renewed mimics a traditional retail set up that seems to encourage purchasing through the showcasing of "best sellers", price cuts, and nudges to 'new' products. Such practices seem to toe the line of a complicated greenness. This notwithstanding, TNF Renewed also is the only of the five brands to employ green coloration to logos and site anchors.

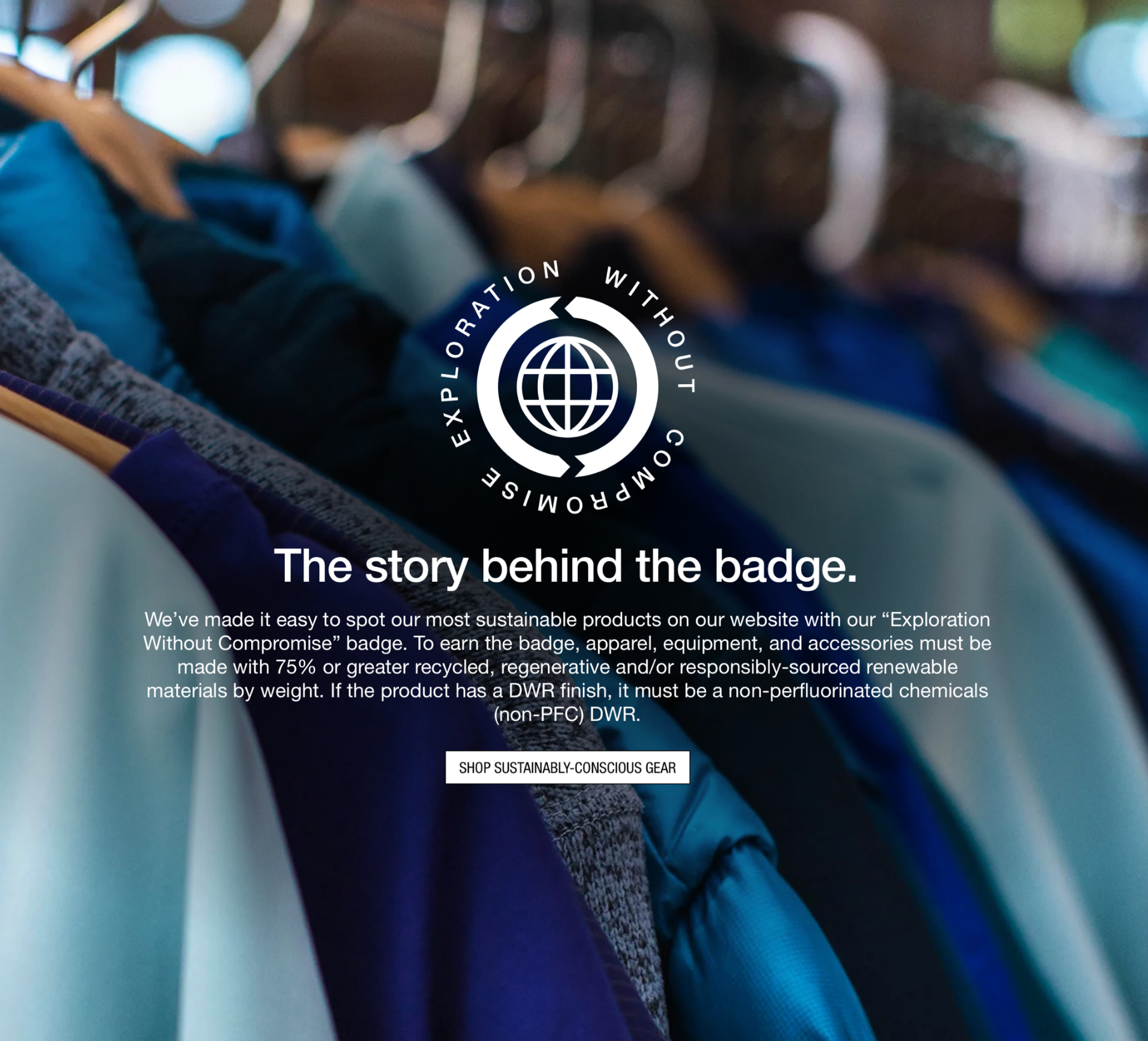

From a language stance, TNF uses an incredibly wide variety of sustainability signals from frequently using the term "Sustainability", "circular", or even combinations of terms. One link reads: "Shop Sustainably-Conscious Gear". Apart from the variety of these buzzwords, TNF nonetheless does have a favorite. The brand most prominently employs "re" words (i.e. recycle, reduce, regenerated, replenish) which tends to indicate that TNF's sustainable alignment is prolonging material or product life or some version thereof. However, by the sheer breadth of terms, it can be difficult to digest what precisely their methodology is. Is this jacket recycled? Remade? Refurbished?

Alternatively, compared to the other brands, TNF appeals more to consumer egoism albeit through environmental means. Research has in fact demonstrated that this is a lucrative strategy. By prominently featuring testimonials or by soliciting email subscriptions by saying "Sign up to help make the planet healthier with your choices", TNF's messaging is more aligned with action calls.

Lastly, TNF exhibits both a creative and commercial orientation to sustainability. While having programs and partnerships aimed at educating designers which demonstrates an action towards sustainability, they also frame their sustainability objectives as long-term goals, investments, and interventions.

Everlane

Sustainable Buzzwords: Transparent; Ethical; Responsible

Primary Appeal: Environmentalism; Altruism

Secondary Appeals: Quality; Community; Innovation

Everlane is known for their minimalist aesthetic and perfection of timeless fashion staples focusing on "ethical sourcing". Unsurprisingly, their website reflects this style featuring a neutral palette accented by the muted tones of their product offerings. Crisp sans serif font styles the copy.

While still on the main page, Everlane's first instance of sustainable messaging appears near the end of the page under the title "Our Promise—Radical Transparency" followed by two tiles that link to "Our Sustainability Initiatives" and "Ethically Made. Designed to Last". By following the first route you are led to a page of alternating mountainscapes or product images and copy. For Everlane, the tenor of the messaging is goal driven and frames their sustainability as something to be attained and built. Indicatively, they articulate their sustainability goals in terms of "lead[ing]", doing "our part" and a "fight" to "make a meaningful difference". In doing so, Everlane constructs an environmental appeal that is undergirded by a sense of teamwork for a better future which evokes a sense that one is participating in doing good through their Everlane purchases.

Then, there is the prominence of "ethics". Framing terminology such as "ethical", "responsible", and "accountable" as their ideals/beliefs, Everlane hints at an undertone of moralistic altruism to their sustainable embodiment. Namely, this is demonstrated through their characterization of selecting their products as the "right choice" for the planet and the frequent use of superlative adjectives. Although other brands such as EF exhibit a sense of moral responsibility as well, it is less noticeable than with Everlane.

This idea of emphasizing the consumer's choice indicates a form of consumer empowerment. But this is not the only way it is achieved. On their "Ethically Made" page, Everlane offers detailed cost breakdowns of several of their products compared to the "traditional retailer. Not only does this establish a rapport (along their lines of "Radical Transparency") by giving the consumer typically guarded information, it also displays that Everlane's price point is cheaper compared to the average comparable retailer and therefore potentially may motivate consumer purchases by indicating that sustainable doesn't always cost more. With this concession of a relatively lower price point, it then becomes clear why Everlane also appeals to quality as part of their sustainability messaging.

Lastly, while the other brands focused on their sourcing and factory partners (which Everlane also does), Everlane highlights the sustainability that is built into their design offices as well. Highlighting that they are LEED certified and utilize renewable energy, this provides a mechanism for Everlane to render sustainable outside of the typically thought parameters or product and supply chains.

Taylor Stitch

Sustainable Buzzwords: Responsibility, Reuse, Reduce

Primary Appeals: Community; Environmentalism; Sourcing; Altruism

Secondary Appeal: Lowsumerism

Contemporary menswear brand, Taylor Stitch (TS), prioritizes workwear and sportswear attire. Taylor Stitch offers a Restitch repair program, and a Workshop community forward small-run program. The Taylor Stitch site emanates bold, masculine colors of gold, olive drab, and workwear blue. A point of note is that the site excellently showcases texture which contributes to the rugged vibe of the brand. Compared to the other four brands, TS more readily uses serif fonts giving it a more traditional feel. TS's sustainable messaging is by far the most concise. Following the trend of using aerial shots of hillscapes as the sustainable image-of-choice, TS opts to orient their sustainable messaging as "Responsibility". In this vein, while brands like Everlane took this to a more moral direction, TS formulates this commitment as more custodial insofar as their aim is to "protect" the environment. While their "Five Pillars or Responsibility" incorporate factors that allude to circularity and ethical sourcing, TS's mode of sustainable practice is more so built on logics of reuse and lowsumerism.

Concepts of reuse are revealed as they highlight products made with "up-cylced cotton", "byproduct-sourced" leather, and their donations of unused fabrics for repurposing. Of course, this messaging is fully in line with TS's Restitch and Repair services. What's more, TS creates an aura of product longevity through consistently reiterating that their goods are durable, repairable, and timeless. This form of messaging certainly contributes to a lowsumerist model as it mitigates the seeming necessity to buy something that is brand new.

One of the comparatively unique aspects of TS is their construction of lowsumerism through community building specifically via consumer collaboration. By offering their Workshop line— small batch lines that consumers can individually fund—in addition to offering fabric polls on their social media, TS is able to operate a system that minimizes the potential for overproduction on one hand, and on the other offers a degree of customization and consumer input to the brand in order to facilitate buy-in to the brand's mission.

Sustainable Personae

While messaging similarities between The North Face and Patagonia were expected due to them occupying the same market, the manner in which the five brands rendered sustainable exhibited several consistencies.

Because the sites featured similar layouts, fonts, and color palettes, the content similarities and junctures were more pronounced. Seemingly minor details such as the typeface are vital in the construction of messages through what Keith Murphy articulates as "typeface ideologies"[8]. As such the ambient fonts work to imply characteristics of the brand in relation to sustainability intentionally or otherwise. While the san serif typeface or EF parallels the luxury brands' en masse shifting to this type style, thus hinting at an alignment to fashionability, in the case of TNF and Patagonia it can be read in line with their technical approach. In the case of Everlane, both of these design details can apply.

Then there are the images. With a caveat for The North Face and Patagonia, sustainable imagery across the five brands incorporated vistas of lush hillsides, expansive oceans, and various aspects of cotton. Additionally, all of the sites featured images of sewing machine operators, farmers, or artisans in progress. Such depictions align with brand constructions of sustainability as more of a creative 'grassroots' endeavor as opposed to a corporate venture .

Additionally, among all of the brands, appeals to environmentalism were prominent. While this may seem obvious, the recognition that sustainability also encompasses other aspects—fair wages for example—demonstrates a thematic priority in how apparel brands (at least in this price point and respective markets) communicate sustainability. From a theoretical marketing standpoint, these firms' also demonstrate a commitment to sustainability as part of their brand identity [9] but also the manner in which they articulate their sustainable orientation contributes to the personality of the brand that is the thing of substance when it comes to consumers.

Images of site menus from top to bottom: The North Face Eileen Fisher, Taylor Stitch, Everlane

Links to the sustainability rundown for each of the brands is found underneath some variation of "About Us" link or closely juxtaposed to it rather than being placed as its own separate pathway. Patagonia is perhaps an exception, but CSR messaging and allusions are rife throughout their page such that it is readily embodied in this fashion.

Consumer Trust

Another connective thread is consumer reassurance, particularly with the brands that portrayed traditionally masculine aesthetics (which were also the more active brands) underscored their products' durability. To this point, the brands that either focus on menswear or had menswear options tended to have more emphasis on data and durability compared to the EF —the womenswear only brand—that used a stronger narrative approach while having resources for consumer product care versus a pre-purchase guarantee. Each selling some iteration of refurbished garments, Patagonia, The North Face, and Taylor Stitch all supplement their products with their Ironclad Guarantee, TNF Warranty, and the Long Haul Guarantee respectively. In a similar capacity that Everlane sought to debunk the myth that sustainability equals higher costs, these brand guarantees function as a mechanism to assuage doubts in the reliability of upcycled or second hand products that in turns deters purchasing.

Along these lines, the ways in which these firms render sustainable is of import to FTC Green Guides. The Green Guides recognize the power in language and imagery when it comes to consumers' reliance on environmental claims and therefore recommend ways to avoid deception. However these guidelines reflect

"...how reasonable consumers likely interpret certain claims. The guides are based on marketing to a general audience. However, when a marketer targets a particular segment of consumers, the Commission will examine how reasonable members of that group interpret the advertisement."

In other words, if a particular target audience is likely to understand a particular articulation of environmentalism as opposed to the general FTC standards, this may simultaneously bolster transparency or conversely offer itself as a loophole for corporations. In either regard, this lends credence to firms' production of a sustainable personality.

Points of Concern

Given the consistent environmental appeals, it is unsurprising that all of the brands at one point framed their manufacturing auctions in regards to "environmental impact". However, in almost all cases, the brands had preferred terms when articulating their sustainable commitments which underscores the degree in which sustainability language is levied to differing ends. In some ways, the relative lack of "zero-waste" verbiage suggests a recognition that these terminologies carry weight. By opting to frame their contributions in terms of some net-impact is indicative of some corporate consciousness that recognizes zero waste as a point of marketing is not congruent with their reduced waste products. Though small, this nuance suggests that these sustainability terms can in fact be delimited by government or some other standardised regulation.

However, breadth in terminology is not the end of the expansiveness of sustainability messaging for these brands and another concern about sustainable language and signaling emerged from the analysis of these brands' copy. On the surface, the brands featured bite-sized copy tiled into the web layout giving the appearance of easy to digest information about the company's values or how your product is being made. But these bits of copy were just the tip of the iceberg as they were usually accompanied by "Learn More" or "Explore" buttons, which certainly contribute to an investigative allure, but nevertheless take you down an Alice-in-Wonderland-style rabbit hole of seemingly endless information about how the company is sourcing its fibers to how they are championing human rights.

Shockingly, although it would seem that some form of codification of terminology might make the waters of sustainability more navigable, this actually may not be the case. In addition to the smorgasbord of text and web pages, these brands tended to reference a variety of certifying bodies (e.g. B Corps, LEED, FSC) to evidence the legitimacy of their sustainable practices. While on one hand these certifying bodies do provide standardized definitions and guidelines for what they oversee, the fact their standards are not necessarily the same therefore does little clarify sustainability consistently and gives consumers yet another layer of information to research before arriving at an understanding of what sustainability means in a particular context. Bearing this in mind, brands must be cognizant of the amount of research work that they can expect their target audience is willing to undertake. Generously, the provision of such extensive information can be read as an attempt towards brand/consumer transparency. Cynically, this could be read as merely performative. If consumers' purchasing behavior mimics their sentiments when considering information such as government policy for example, it may very well be difficult to research or venture beyond what they perceive to be the status quo or comfortable [10].

Implications and Limitations

At a glance, this survey indicates that sustainability cannot be chalked up to a set of a few buzzwords, but rather is a complex system of social, ecological, and economic relationships. What's more, the lexicographical paintings of sustainability are apt to vary beyond this market sample underscoring the expanse of varied sustainability messaging. If nothing else, the portrait of sustainability does not seem to be tied to an echelon of consumers or a particular consumer type, but rather a consideration by which the brand can adapt itself as sustainable.

Inasmuch as this survey is limited by the fact that the surveyed brands are based coastally in the US, this fact simultaneously demonstrates how regionality may inform how sustainability is rendered but also showcases how these messages and presentations are incongruous despite regional proximity.

This research potentially foregrounds deeper consideration for B2C sustainable aesthetics that can progress understanding in the sustainable socialization of consumers and the construction of sustainable identities of firms within (and conceivably external to) the fashion industry especially in areas of marketing, graphic design, and product development. While this study is qualitative and limited in size, the dataset can be expanded and processed quantitatively to parse any statistical significance that may be present in these modes of sustainable presentation. Additionally, future research embedded from the consumer perspective can be conducted as a means to gauge receptivity and the efficacy of these aesthetics and messaging choices.

Notes:

Escobar, A. (2018). Designs for the Pluriverse: Radical Interdependence, Autonomy, and the Making of Worlds .Duke University Press.

Raworth, K. (2017). Doughnut Economics: Seven Ways to Think Like a 21st-Century Economist. Chelsea Green Publishing.

Rissanen, T., & McQuillan, H. (2018). Zero Waste Fashion Design. Bloomsbury.

Cf. Bechky, B. (2003). Sharing Meaning Across Occupational Communities: The Transformation of Understanding on a Production Floor. Organization Science, 14(3), 312-330.

Irani, L. (2019). Chasing Innovation: Making Entrepreneurial Citizens in Modern India. Princeton University Press.

Boellstorff, T., Taylor, T. L., Pearce, C., & Nardi, B. (2012). Ethnography and Virtual Worlds: A Handbook of Method. Princeton University Press.

Bubonia, J. E. (2017). Apparel Production Terms and Processes. Bloomsbury Academic.

See for example Loef, J., Pine II, B. J., & Robben, H. (2017). Co-creating customization: Collaborating with customers to deliver individualized value. Strategy & Leadership, 45(3), 10-15.

Murphy, K. (2017). Fontroversy! Or, How to Care about the Shape of Language. In J. Cavanaugh & S. Shankar (Eds.), Language and Materiality: Ethnographic and Theoretical Explorations (pp. 63-86). Cambridge University Press.

Aaker, D. (1995). Building Strong Brands. Free Press.

Muller, J. (1997). What is Conservative Social and Political Thought? In Conservatism: An Anthology of Social and Political Thought from David Hume to Present (pp. 1-31). Princeton University Press.

Matt Porter, Sustainability Research Intern

Matt Porter, is an educator, design researcher, and sociocultural anthropologist with an emphasis on fashion theory, epistemologies of dominance, and the US military. His approach maps critical theory onto strategies of design and material production. Currently, his works-in-progress include inquiry into the socio-legal implications of political fashion and prototyping models aimed at reconstituting US garment manufacturing. At Unbuilt Labs, Matt will be investigating consumer sentiment and receptivity to sustainable business schemas and how fashion brands can meet consumer demands with ethical yet effective business models.

Parsons School of Design, MA in Fashion Studies, 2019

University of North Texas, BA in Fashion Design, 2016